Dice rolls in Traveller

The “Trying again” section was initially incorrect, and said that a task chain was better than pushing the roll in some situations.

When a PC wants to do something, the GM might call for a roll to see whether they succeed or, if success or failure is a given, how well they do.

In Traveller, the player rolls 2d6,

adding their characteristic modifier, skill level (or a penalty of -3

if they lack the skill entirely), and any other modifiers the rules

specify, generally against a target number of 8. In situations where

there is no relevant skill, the player just adds their characteristic

modifier: for example, forcing a door open would just be

2d6 + Strength Mod.

The average result for 2d6 is 7, but the usual

difficulty target is 8. The average characteristic modifier is 0, but

finishing character creation with skills at level 1 or 2 is easily

doable, so almost all characters do have situations where they have

even-or-better odds. Even odds isn’t that great in a risky situation

though, so the rules implicitly encourage players to seek out other

bonuses, or to change the situation to be safer.

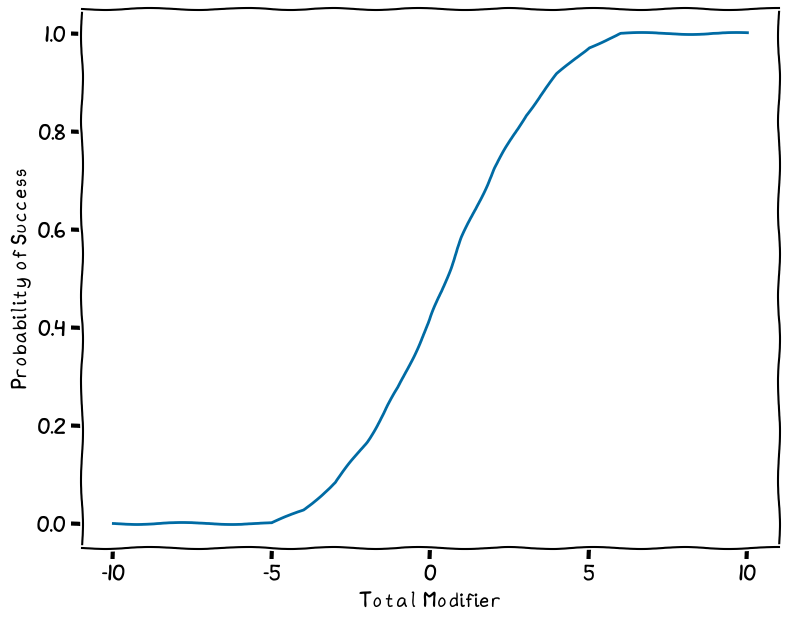

For the graphs in this post, I’ve make some assumptions about the ranges of modifiers:

-

The characteristic modifier ranges from -3 to +3 (which is the case unless you’re using the variant rules for extreme characteristic scores in the Traveller Companion)

-

The skill level modifier is -3 for an unskilled character, or ranges from 0 to +3 for a skilled character

-

Other miscellaneous modifiers specified in the rules range from -4 to +4

So the total modifier for a roll ranges from -10 to +10.

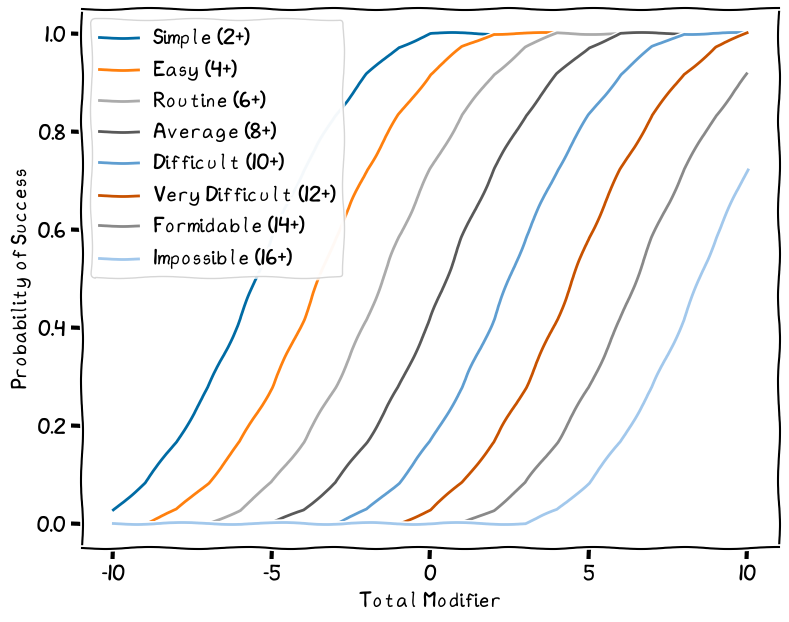

Difficulty levels

Checks have eight difficulty levels, with the target number increasing by 2 every level from Simple (2+) to Impossible (16+).

On the one hand, I like having different difficulty levels to pick from. On the other hand, this feels like too many. I’m a big fan of only rolling when the outcome is in doubt, so I’m not sure when I’d ask for a roll for a Simple or Easy task. Even a Routine task feels a bit much. I’d probably have the PCs succeed automatically at all of those (though, with a caveat: see the next section on timeframes).

“Impossible” is also misnamed, as you just need a +4 total modifier, which is achievable with a bit of luck in character creation, to have a chance of success: “impossible” should mean “impossible”.

Rolling a 16 won’t let you punch a hole through a starship with your bare fists.

Timeframes

One thing I like a lot about the Traveller task check system is that it has rules for increasing or reducing the difficulty of a task check by going faster or slower. In most systems, that’s kind of up to GM fiat, but here it’s codified.

The timeframes are:

1d6seconds1d6combat rounds10×1d6seconds1d6minutes10×1d6minutes1d6hours4×1d6hours10×1d6hours1d6days

There are a few small examples given for each. For example, applying first aid takes minutes, whereas repairing a damaged ship takes tens of hours.

A player can chose to move up or down on the timeframes, doing a check faster or slower than usual. Each step moved up (going faster) adds a cumulative -2 modifier; each step moved down (going slower) adds a cumulative +2 modifier.

So, while I would not normally make someone roll for a Routine task, I likely would still have them roll if they were doing an Average task one step slower than usual.

My only small complaint with the timeframe rules is that I wish this was explained as adjusting the difficulty level of the check up or down, rather than as adding a modifier. The maths is exactly the same, but it feels inconsistent with the rules for doing multiple tasks at once, which are explained as adjusting the difficulty level.

Effect & static target numbers

The “effect” of a task check is by how much the player beat (or failed to beat) the difficulty. So, a roll of 9 has effect 3 if the check is Routine, 1 if the check is Average, -1 if the check is Difficult, and so on.

There’s an optional rule for using the effect to pick a degree of success, if the situation requires more nuance than just a binary pass or fail:

- Exceptional Failure: the check fails with effect -6 or less

- Average Failure: the check fails with effect -5 to -2

- Marginal Failure: the check fails with effect -1

- Marginal Success: the check passes with effect 0

- Average Success: the check passes with effect 1 to 5

- Exceptional Success: the check passes with effect 6 or more

We’ll see these thresholds again when discussing task chains.

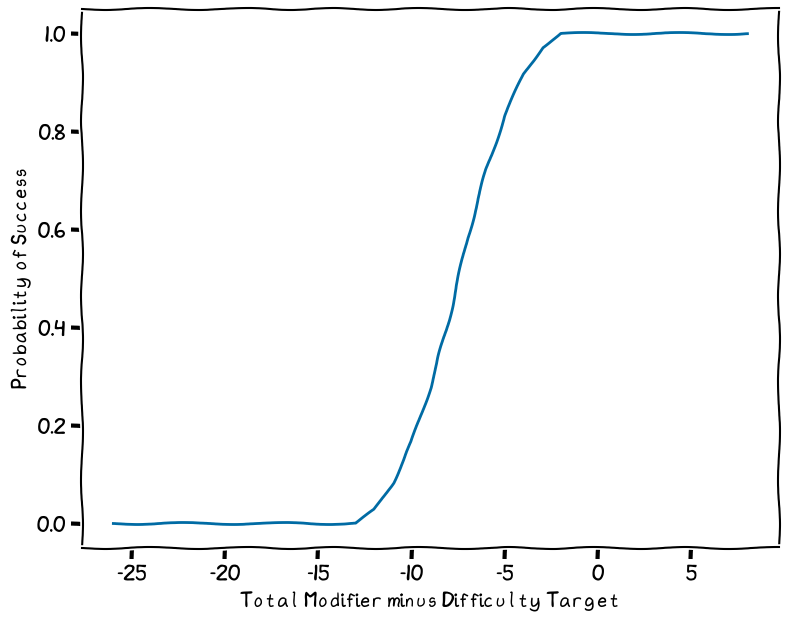

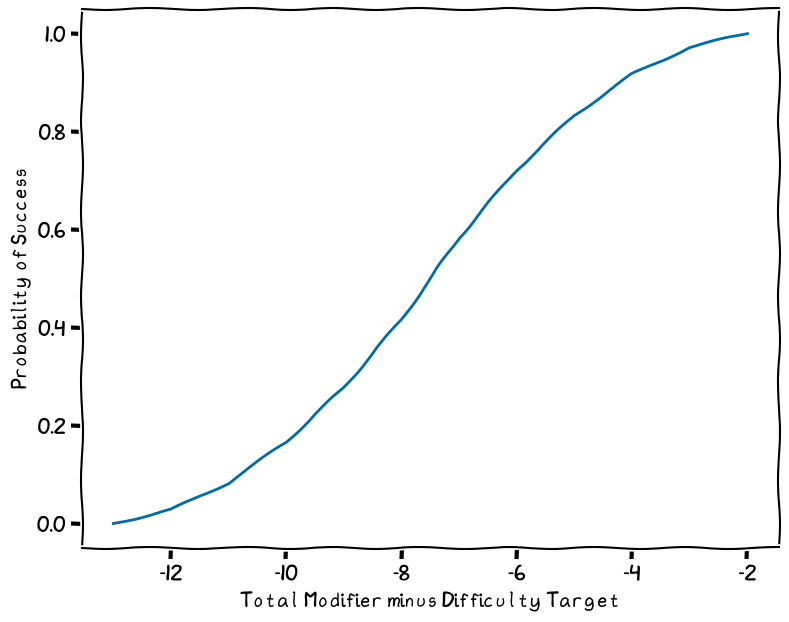

An alternative way to think about Traveller task checks is that you’re trying to roll an effect of 0 or more. So, there’s a fixed target number you want to equal or beat, and the GM has eight possible penalties he can subtract from your roll depending on the difficulty of the situation.

Is that a useful way to look at the rules? When actually playing, probably not. But for this post, it means I don’t have to draw eight separate difficulties in all of the graphs.

So the range on the X axis of the graphs is now -26 (an unskilled character with a -3 characteristic modifier, with a -4 modifier from other rules, attempting an “impossible” task) to 8 (a character with a +3 characteristic modifier and +3 skill level modifier, with a +4 modifier from other rules, attempting an easy task).

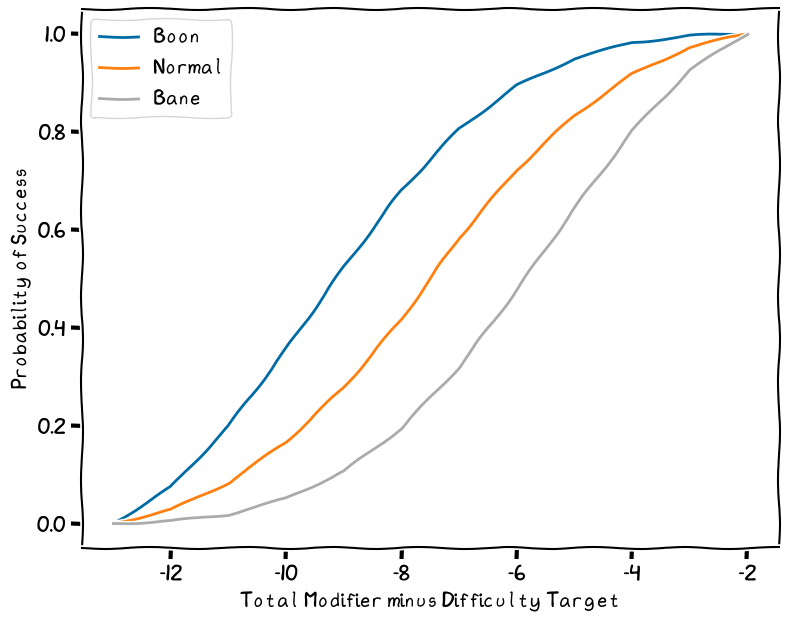

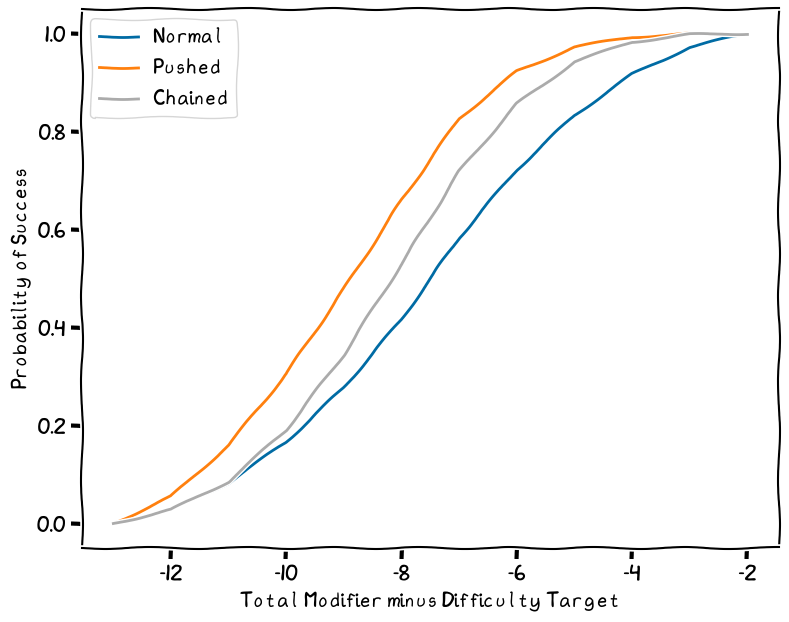

But we can trim that range down to -13 to -2, as everything lower has a 0% chance and everything higher has a 100% chance:

This is the formulation we’ll use going forwards.

Situational advantages and disadvantages

Let’s say that a PC is trying to hotwire a locked-down jump drive.

Perhaps our would-be pirate has an easy time of it. Maybe they’re blessed with a particularly competent assistant; or there’s a detailed diagram explaining exactly how the lock works.

On the other hand, perhaps they have an unusually hard time. Maybe the engine room is really small and awkward, so the PC can’t get a good look at the mechanism; or they have shoddy tools.

In these cases, the skill-based task itself (hotwiring the jump drive) is exactly the same, it’s just the circumstances around it which vary. So making the task check easier or harder doesn’t really fit.

To handle this sort of situational effect, the GM might give the

player a boon die or a bane die. The player now rolls

3d6, keeping the better (or worse) of the two

rolls. Or the GM might say that success or failure is

impossible given these additional situational factors, and so remove

the roll entirely.

Boon and bane dice cancel out and do not stack: a check with one boon and one bane is rolled normally; a check with two boons is rolled with one boon; a check with two boons and one bane is rolled with one boon; and so on.

Task chains

Let’s say that the PCs are preparing to jump to another system: the astrogator plots the route, then the engineer inputs it into the jump drive. The quality of route should affect how well the engineer is able to configure the jump drive, and Traveller handles this sort of thing with “task chains”: a sequence of connected task checks where the effect of a check applies a modifier to the next check in the chain.

- If the previous check failed with effect -6 or less, the current check gets a -3 modifier

- If the previous check failed with effect -5 to -2, the current check gets a -2 modifier

- If the previous check failed with effect -1, the current check gets a -1 modifier

- If the previous check passed with effect 0, the current check gets a +0 modifier

- If the previous check passed with effect 1 to 5, the current check gets a +1 modifier

- If the previous check passed with effect 6 or more, the current check gets a +2 modifier

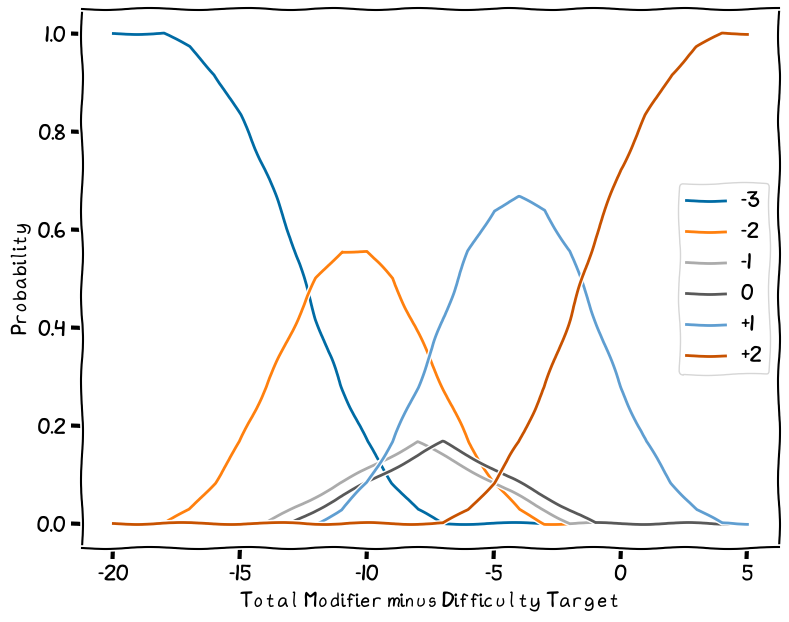

First, let’s have a look at the chance each modifier has of coming up:

I find this pleasantly asymmetric.

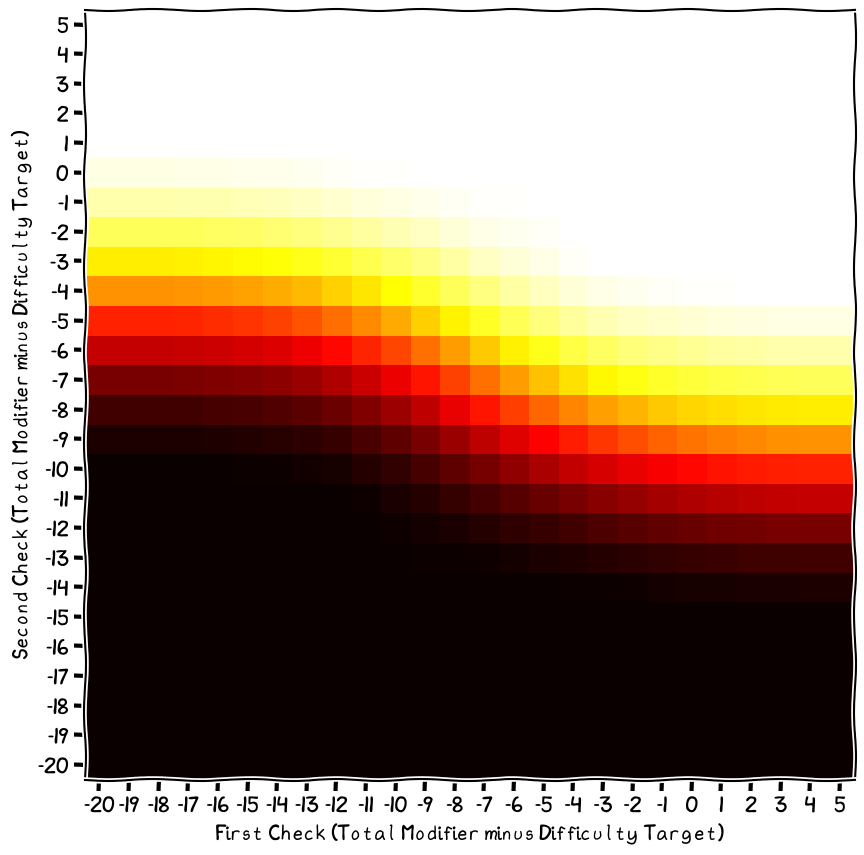

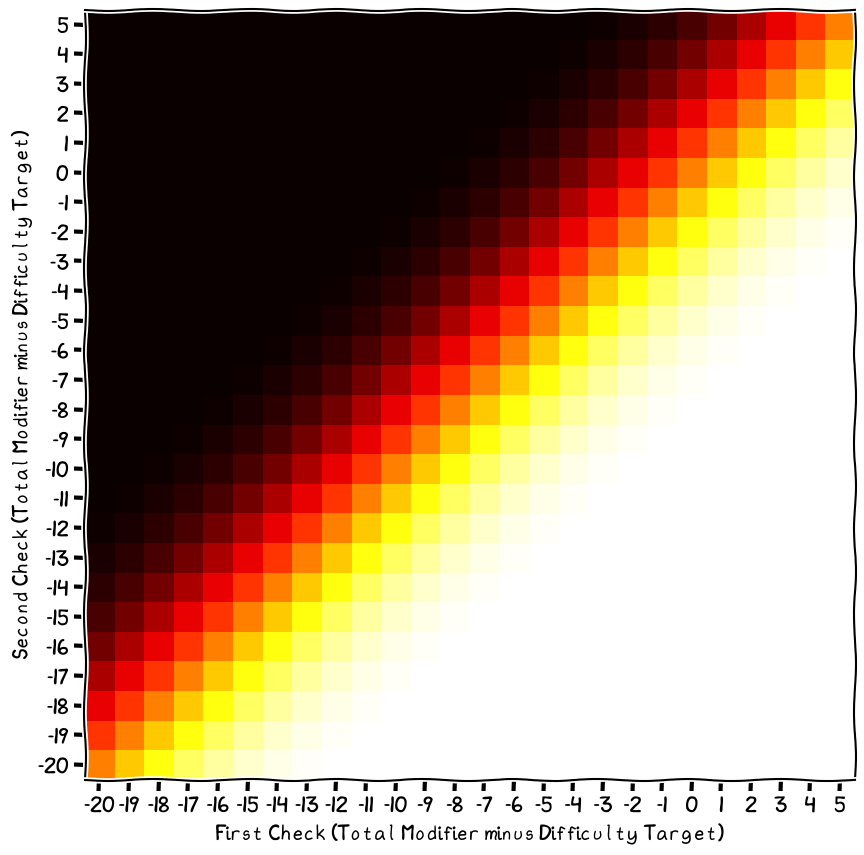

Now, let’s look at the chance of the second task in a chain

succeeding. Here, the Total Modifier in the Y axis does not include

the task chain modifier from the first check (that’s why this is a

heatmap and not just a line chart). The colour shows the chance of

succeeding on the second check: lighter is better.

An interesting thing to note here is that because the positive and

negative modifiers from the first check are bounded, there are plenty

of cases where the result of the second check doesn’t depend on the

result of the first check at all. For example, if the second check

has a Total Modifier minus Difficulty Target of 1, they will succeed

no matter how badly the first check goes. But if the second check has

a Total Modifier minus Difficulty Target of -15, they will fail no

matter how well the first check goes.

So, with a huge penalty, the players will need to seek out some other advantage: like going more slowly and carefully, reducing the difficulty at the cost of time; or finding some advantage which gives them a boon.

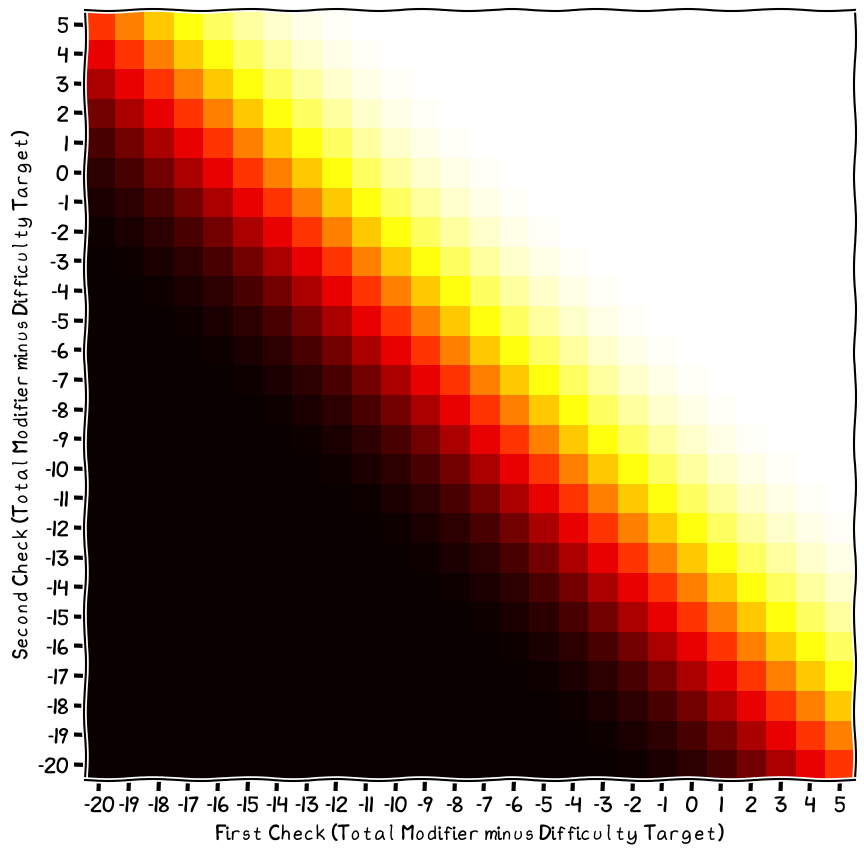

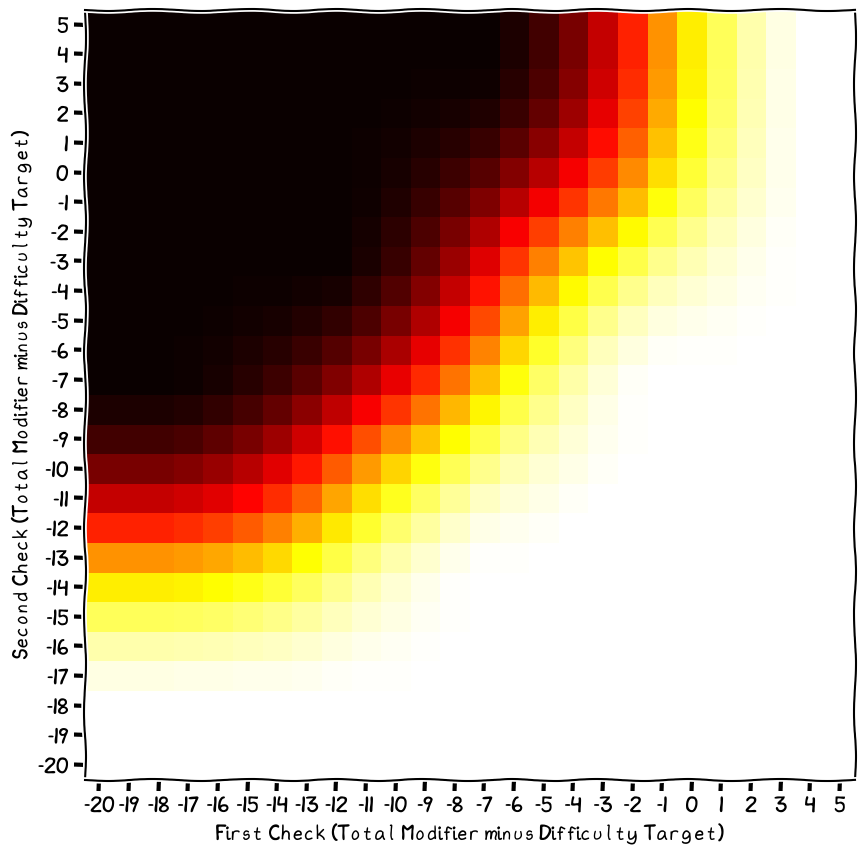

Compare with what it would look like if the second check just used the effect of the first check as a modifier directly:

Very different!

Trying again

Unlike Call of Cthulhu, Traveller has nothing like pushing a roll. So if you want to allow a player to try a task check again, you’ll have to improvise.

I think either the pushed-roll system (try again, but with significantly worse consequences for failure) or a task chain (try again, but with a modifier based on how badly you failed) would work, and each probably makes more sense in different situations.

Pushing a roll is always better than doing a task chain. Because the first roll failed, the second roll in the chain will always have a negative modifier; whereas a pushed roll is just a straight re-roll. So keep that in mind if the character is really poorly suited to a situation: perhaps they should first have to climb out of the hole they dug for themselves, rather than just get a second attempt!

For example, if the PC is trying to repair something, and they badly fail, then a task chain makes sense as they now need to repair the original damage and what new damage they just caused. Whereas if the PC is trying to find a target in some surveillance tapes, failure doesn’t destroy the tapes, but trying again might cost them much more time than they’re comfortable spending, so pushing the roll makes more sense.

Going head-to-head

For opposed checks, the two characters simply roll, and the one with the higher effect wins. Though oddly, at least to me, the degree-of-success rule is not used here: it’s just the raw effect number.

Here the colour shows the first character’s chance of succeeding despite the second character’s opposition: lighter is better.

Opposed checks are used if two characters are directly competing with or opposing each other. They’re generally not used in combat (except for grappling), where the defender imposes a negative modifier to the attacker’s roll instead, rather than themselves rolling to resist. I think I prefer opposed combat rolls, but systems which do them seem pretty rare.

If it did use the degrees of success, it would look like this:

This looks like it could be an interesting mechanic to me! The second character’s ability to oppose is limited, and so the first character has better odds overall.

But, interesting as it might be, it’s not a rule. Maybe a “negative task chain” would make sense as a house-rule for asynchronous conflicts?

The golden rule

As always, before rolling anything, ask if a roll is really needed here.

If the task is challenging but the PC can spend as long on it as they want, shouldn’t they just automatically succeed?