Izirion's Enchiridion of the West Marches

Izirion’s Enchiridion of the West Marches is a source book for West Marches style play, which I kickstarted earlier this year. It’s written for fifth edition D&D, but has an appendix giving some guidance for using it with OSR systems.

In addition to the usual rules, setting, and examples, the book has frequent asides explaining why something has been designed the way it has been, or to give further advice. This is great, because if you internalise these asides, you can more easily deal with situations which the rules don’t cover. You don’t have to guess at the intention of the rules from the text, it’s right there in front of you.

For example, a section on worldbuilding has this aside on why you should keep the “danger level” within each region more-or-less consistent:

What’s in the book

13 pages of frontmatter and introduction, giving an overview of the West Marches style of play for people unfamiliar with it, also covering safety tools and some potentially sensitive topics that might come up in your game.

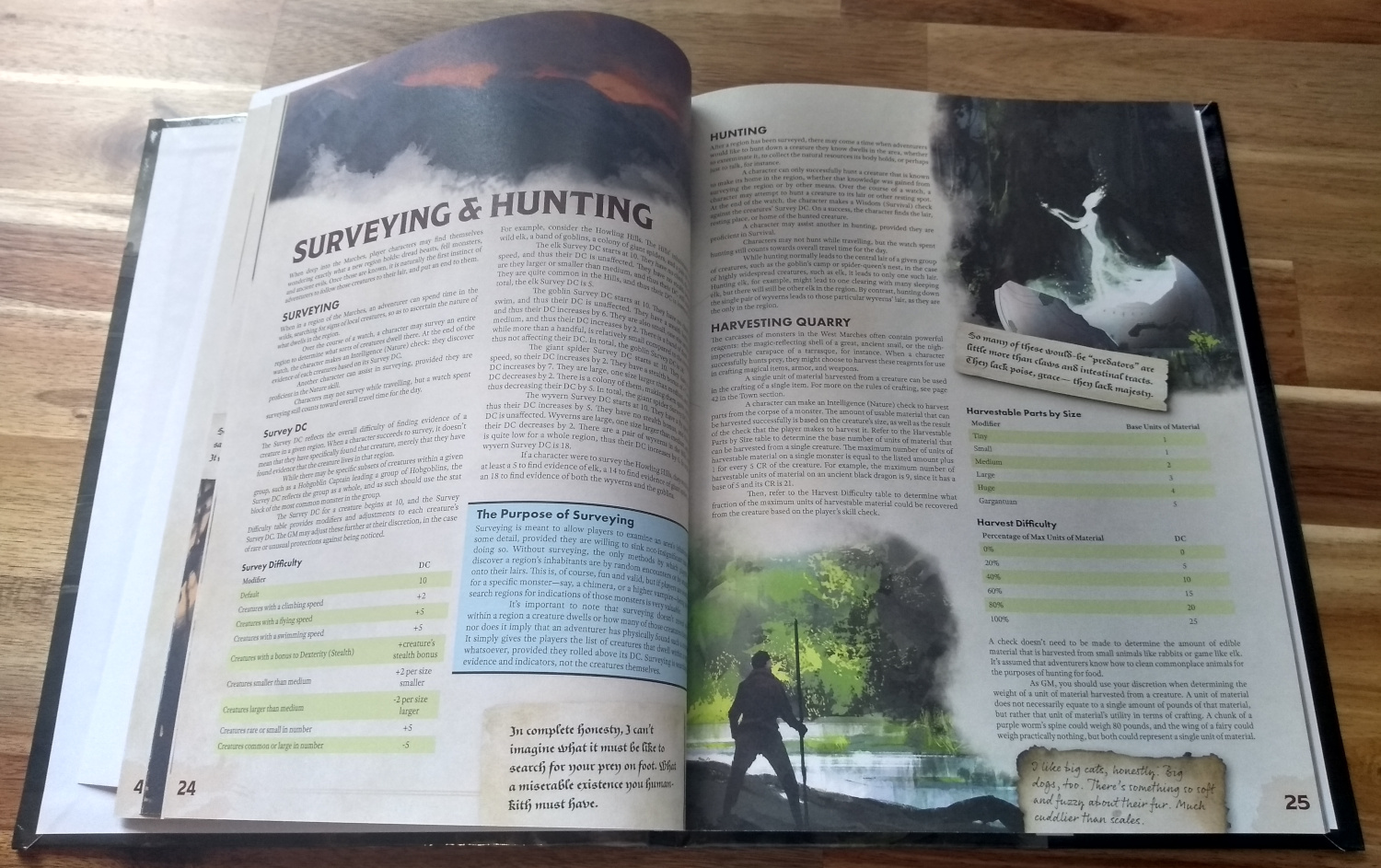

14 pages on survival and travel, broken down into five large subsections on travel (including getting lost), weather, food & water (including what happens if you consume unclean food or water), surveying & hunting, and hazards (both weather and terrain hazards). 14 pages to cover all that doesn’t sound like much, but the text is very small and the pages are quite large, so there’s a lot of content here.

Travel in the Marches is dangerous. Navigation is by compass directions and visible landmarks, not fuzzy things like “the temple we passed last week”. Even putting aside the possibility of getting caught in an avalanche or a blizzard, you can get lost, encounter monsters, or run out of resources.

30 pages on worldbuilding, broken down into four large subsections on the town (the safe home base of the PCs), regions, factions, and dungeons.

Since a party might travel through the same region in the Marches many times, these locations have to work for repeat visits and for differing character levels. While regions and dungeons will have a broadly consistent danger level, as mentioned above, they can have isolated pockets of danger, giving a challenge for returning adventurers. Ben Robbins, the creator of the West Marches style, called these “treasure rooms”, and the Enchiridion covers not only treasure rooms, but also how to change dungeons and regions over time if (for example) the party clear out the current inhabitants and then leave it open for someone else to move in.

Unlike regular D&D, a dungeon isn’t a one-time challenge in the Marches.

13 pages on narrative, covering the mechanical basis of emergent narrative (and, I’m happy to see, the authors agree with me on not fudging dice), how to create narrative through lore and encounters, and why a comprehensive PC backstory is actually a hinderance in a West Marches game.

Often, players arrive at the game table for the very first session with an idea of who they want to play, and even with a backstory written up for the GM to use to generate relevant story hooks. But that approach doesn’t work well in the West Marches, because who you were before coming to the town doesn’t matter. The story comes from what the PCs do and how they change; who they were merely informs how they start out.

5 pages on player options, which is probably the least useful section if you’re not using something D&D-based. It gives some feats and class changes, and argues that you should use XP levelling (rather than milestone levelling), and that you can give XP for exploration as well as for combat.

If your system of choice doesn’t use XP, levels, or classes, then this section doesn’t have much to offer.

23 pages of worked examples, across two sections, the first building an example swamp region, a faction, and a small dungeon; and the second building a more fleshed-out faction: a coven of hags and their hangers-on.

Examples are always great to have. I find a good worked example really helps me understand how the system is meant to be used. In source books I usually like to see sample scenarios, but the player-driven nature of the West Marches doesn’t lend itself so well to that style of play: a dungeon is more useful here than a story.

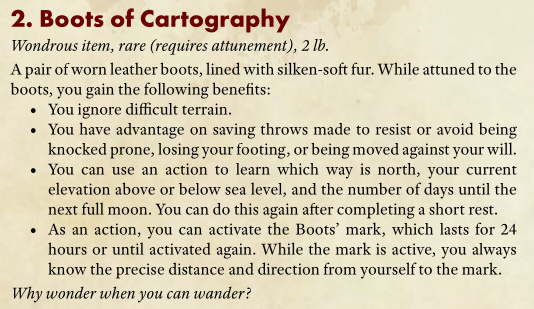

3 pages of 20 magic items, but I’m not much of a “magic item” person. Magical boots which let you ignore difficult terrain, or a magical apron which makes things in its pockets rot more slowly, or a magical cloak which let you teleport are all in danger of making magic feel too mundane in my opinion. I’m fine with magical tools (for example, in my current D&D game I have a magnifying glass which lets my character see magic much like the Detect Magic spell) and magical weapons and armour, but magical clothes are just a step too far.

In a setting where resource management is key, I feel that magic needs to be risky, limited, or both. Not just something you get by putting on a pair of boots.

3 pages of 20 crafting materials these, on the other hand, I do like. Each material has a short paragraph of flavour text and some effects, like “all objects made from Ignan brass glow with a dim reddish light, out to a radius of 5 feet.”

I can imagine going out on a quest to an abandoned dwarven mining outpost, to get some rare ore, and bring it back to the town to have some special item made. That’s an adventure right there.

2 pages on OSR conversion, covering lethality, difficulty classes, saving throws, encumbrance, conditions, and monsters. Since OSR systems are all slightly different, this section gives rules of thumb and not exact formulae for, e.g., how much damage being hit by an avalanche should do. This section looks like it’ll be useful for converting to non-D&D-based games too.

And finally, 16 pages of summaries, covering D&D conditions, and a big collection of all the tables used elsewhere in the book. It’s mostly tables, actually. I’ve not tried using this in game yet, but the tables are grouped by topic, so it seems like it’d work well.

My overall thoughts

I’ve not run a game with the book yet, but I’m looking forward to trying it out. The survival & travel chapter in particular has opened my eyes to how to make traipsing through the wilderness more interesting than just “you walk through the forest for three days and roll get lost.”

The book is a bit D&D-specific, but it would be unfair to criticise it for that because it didn’t pretend to be otherwise. In fact, by including a chapter with tips on how to convert it for OSR systems it’s already more system-neutral than most modern D&D material.

I only really have two major complaints about the book.

Firstly, the text is very small. Each page is very dense. I think the book could easily have coped with, say, twice the font size and double the number of pages, which would bring it up to 252 pages. Though, it is a bit verbose in parts, so a second edition with some editing likely wouldn’t even be as long as that.

Secondly, it’s a hardback, but with a glued binding rather than sewn. So the pages don’t lie flat when the book is open. This makes it just that bit more awkward to use in the game, where if you leave it lying open on the table you may need to press it down to read a bit of text, or a page may flip over by itself.

Those are pretty small problems, and I’ll probably use the PDF in-game, or print out specific bits to glue to a screen, rather than use the physical book directly.

So, unless those are deal-breakers for you, this book is worth checking out.